History of Madrid

Although it is believed that the Roman Empire founded a settlement where the city of Madrid currently lies, the first documented records of Spain’s capital date back to the ninth century AD. The Iberian Peninsula was occupied by the Moors. Since then the city has undergone numerous changes which can be seen in its current appearance.

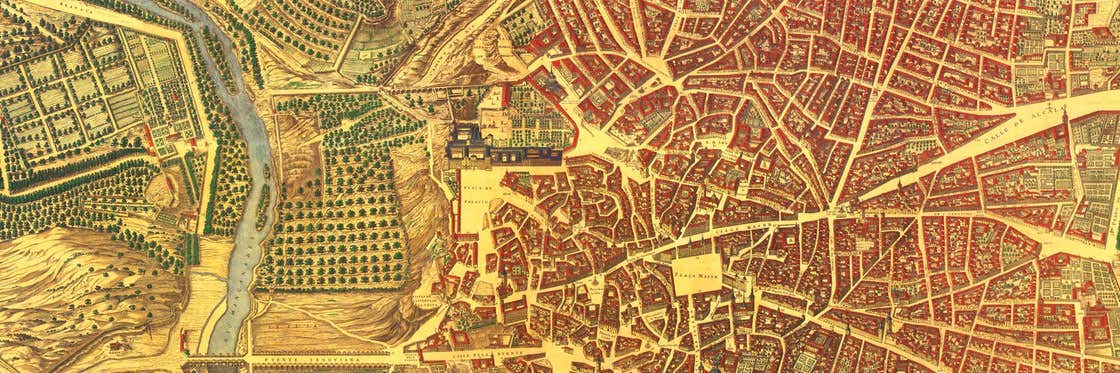

Muhammed I, Emir of Córdoba from 852 to 886, commissioned the construction of a fortress on the banks of the Manzanares River and called it “Mayrit”.

The stronghold was built where the Royal Palace of Madrid presently sits. The citadel was strategically built on top of a hill, with views over the Sierra de Guadarrama. From this location, the Moors could organize incursions against the northern Christian kingdoms. This practical construction became the origin of Madrid.

The meaning of “Mayrit” isn’t completely clear, although it seems to be the hybrid of two place names; “matrice” meaning fountain in Mozarabic language and “majrà”, meaning riverbed or course of a river in Arabic. Both words refer to the abundance of water, rivers and groundwater there was in this part of Spain.

The citadel was temporarily conquered by Ramiro II in 932, but the Moors managed to reconquer the castle until they were overthrown by Alfonso VI of León and Castile in 1085, on his way to occupy Toledo.

Favoured by the monarch’s measures to repopulate the territory, particularly by the compilation of laws called Fuero from 1202, the city began to grow around the fortress during this period.

In 1339 and 1340, Alfonso XI convened the court of the Kingdom of Castile (Cortes del Reino de Castilla) in Madrid, as Henry III of Castile would also do.

Madrid, capital of Spain

Madrid did not become an influential city until Philip II of Spain transferred the capital from Toledo to Madrid in 1561. When the Court had been moved, it became patent that urban reforms were needed and soon suburbs grew outside its Medieval walls which changed the history of the city.

The number of inhabitants grew from 4,060 in 1530 to 37,500 in 1594. In April 1637, there were 1,300 “legitimate poor and disabled” people and 3,300 beggars in the Courts. Most of them were foreigners, former soldiers and pilgrims from Santiago de Compostela in Galicia. These made up, along with, the swindlers and ruffians, the bottom of Madrid’s social pyramid. The population’s discontent due to bread shortages and inflation was exploited by certain parties to encourage riots, for example, “The Riots of the Cats” in Madrid.

The royal court attracted many Spanish and foreign artists and the city became the artistic and literary hub in Spain. The most impressive buildings of Madrid de los Austrias (the name used for the old city centre), include the Plaza Mayor, the Town Hall, certain churches and the court jail.

War in Madrid

During the eighteenth century, Madrid took part in the War of the Spanish Succession, caused by the death of Charles II, who died without an heir. The empire was sought after by the royal houses of Austria (Habsburg), France (Bourbon) and Bavaria (Wittelsbach). Madrid had supported the Bourbon family since 1706 and when Louis XIV of France (House of Bourbon) finally sent his grandson to Madrid to become King Philip V of Spain, so the country was led by a member of the House of Bourbon.

As a way of thanking Madrid for its support, Philip V commissioned new palaces and buildings, including the Bridge of Toledo, and the Royal Palace of Madrid (1737), which was built to replace the Royal Alcazar, burnt down in 1734. Ferdinand VI of Spain and especially Charles III put great efforts to modernize the city, for example, by cleaning the streets, installing stone pavements, introducing streetlights and employing people to survey the streets at night, among many other interesting measures. Charles IV continued with these reforms, but on a smaller scale.

Madrid’s society also changed, it became more open to artisan and liberal families and was no longer jumbled and multifarious. Nevertheless, the lower classes were still exposed to periodic famines and their discontent led to political turmoil, like the Esquilache Riots (March 1766) and the Mutiny of Aranjuez (1808). That same year, Madrid’s working classes would fight against the French on the 2 May during the Dos de Mayo uprisings.

The efforts made by the Bourbons to transform Madrid into a modern and developed city were interrupted by the Napoleonic Wars. The city didn’t fully recover until the 1830’s.

Between 1840 and 1850, many old convents and church-owned estates that had been bought by traders, landowners, liberal workers and financiers due to the Desamortización Eclesiástica of Mendizábal in 1836 (Mendizábal's confiscation of church-owned property) were demolished and new neighbourhoods were established. However, Madrid was practically the same size it had been during the Habsburg period.

Modern Madrid

Madrid’s population did not increase thanks to the city’s industrialisation, as most of the industrial companies in the twentieth century were still very traditional and only met the city’s requirements. From 1920 onwards, immigration led to major demographic changes and in 1930, 46.9% of the capital’s inhabitants had been born outside Madrid.

After World War II, Madrid, besides being a key consumer market, went through a period of modernisation in which large companies were set up and certain industries like the chemical-pharmaceutical, metallurgical and electromechanical began to develop.

Currently, six million people live in Madrid's metropolitan area and it is one of the most important cities in Europe. And in recent years it has played host to important congresses, such as the 2019 COP25.

And the major concerts and sporting events celebrated in the city, means that the neighbourhoods of Madrid are filled with music and entertainment - making the city an unmissable destination for both short breaks and longer trips.